Ever the innovator, Santa Fe was one of the pioneers in intermodal freight service, an enterprise that (at one time or another) included a tugboat fleet and an airline, the short-lived Santa Fe Skyway. A bus line allowed the company to extend passenger transportation service to areas not accessible by rail, and ferry boats on the San Francisco Bay allowed travellers to complete their westward journeys all the way to the Pacific Ocean. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway officially ceased operations on December 31, 1996 when it merged with the Burlington Northern Railroad to form the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway.

History

Startup and initial growth

The railroad's charter, written single-handedly by Cyrus K. Holliday in January 1859, was approved by the Kansas' territorial governor on February 11 of that year as the Atchison and Topeka Railroad Company for the purpose of building a rail line from Topeka, Kansas, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and then on to the Gulf of Mexico; the original eastern terminus was Atchison, Kansas, slightly northeast of Topeka, hence the name. On May 3, 1863, two years after Kansas gained statehood, the railroad changed names to more closely match the aspirations of its founder to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. The railroad broke ground in Topeka on October 30, 1868 and started building westward where one of the first construction tasks was to cross the Kaw River. The first section of track opened on April 26, 1869 (less than a month prior to completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad) with special trains between Topeka and Pauline. The distance was only 6 miles (10 km), but the Wakarusa Creek Picnic Special train took passengers over the route for celebration in Pauline.

The Santa Fe trademark in the late 1800s incorporated the British lion out of respect for the country's financial assistance in building the railroad to California.

Building across Kansas and eastern Colorado may have been technologically simple as there weren't many large natural obstacles in the way (certainly not as many as the railroad was about to encounter further west), but the Santa Fe found it almost economically impossible because of the sparse population in the area. To combat this problem, the Santa Fe set up real estate offices in the area and vigorously promoted settlement across Kansas on the land that was granted to the railroad by Congress in 1863. The Santa Fe offered discounted passenger fares to anyone who travelled west on the railroad to inspect the land; if the land was subsequently purchased by the traveller, the railroad applied the passenger's ticket price toward the sale of the land. Now that the railroad had built across the plains and had a customer base providing income for the firm, it was time to turn its attention toward the difficult terrain of the Rocky Mountains.

Crossing the Rockies

Leadville was the most productive of all of the Colorado mining regions. Mining in the area began in 1859, first for gold and then two decades later for silver. Several of the Santa Fe's board of directors (along with President Strong) sought to capitalize on the need to supply the mining towns of Colorado and northern New Mexico with food, equipment, and other supplies. To that end, Santa Fe sought to extend its route westward from Pueblo along the Arkansas River, and through the Royal Gorge in 1877. Royal Gorge was a bottleneck along the Arkansas too narrow for both the Santa Fe and the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad to pass through, and there was no other reasonable access to the South Park area; thus, a race ensued to build rail access through the Gorge. Physical confrontations led to two years of armed conflict, essentially low-level guerrilla warfare between the two companies that came to be known as the Royal Gorge Railroad War. Federal intervention prompted an out-of-court settlement on February 2, 1880 in the form of the so-called "Treaty of Boston" wherein the DRGW was allowed to complete its line and lease it for use by the Santa Fe. The DRGW paid an estimated $1.4 million to Santa Fe for its work within the Gorge and agreed not to extend its line to Santa Fe, while the ATSF agreed to forgo its planned routes to Denver and Leadville.Also looking to the south, an initial outlay of $20,000 was authorized on February 26, 1878 for the construction of a rail line south from Trinidad in order to "..seize and hold Raton Pass." The location of the route was nearly as crucial to the venture's success as was the actual track construction. W. R. "Ray" Morley, a former civil engineer for the (D&RG) hired by the ATSF in 1877, was given his first assignment to secretly plot a route through the pass (it was feared that any activity in the area would lead the D&RG to construct a narrow gauge line over the Pass). Additionally, Strong learned that the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP) had introduced legislation to block the Santa Fe's entry into New Mexico. Undaunted, Strong obtained a charter for the New Mexico and Southern Pacific Railroad Company and immediately sent A. A. Robinson to Raton Pass. From February to December 1878 work crews struggled to build the line between La Junta and Raton, and the first Santa Fe train entered New Mexico on December 7.

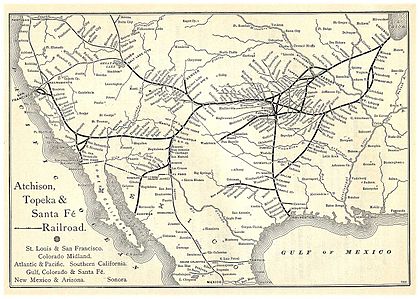

A comparison map prepared by the Santa Fe Railroad in 1921 showing the "The Old Santa Fé Trail" (top) and the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad and its connections (bottom).

Facing the competition

While construction over the Rockies was slow and difficult due to the logistics involved, in some instances armed conflicts with competitors arose (such as with the D&RG in Colorado and New Mexico, and — after capturing the Raton Pass — the SP in Arizona and California, as exemplified in the "frog war" between SP and Santa Fe subsidiary the California Southern Railroad at Colton, California in September 1883). The troubles for the railroad went far beyond skirmishes with rival railroads, however. In the late 1880s, George C. Magoun, who had worked his way to become Chairman of the Board of Directors for the railroad, was progressively losing his own health. In 1889 the railroad's stock price, which was closely linked in the public's eye with the successes of the railroad's chairman, fell from nearly $140 per share to around $20 per share. Magoun's health continued to deteriorate along with the stock price and Magoun died on December 20, 1893. The Santa Fe entered receivership three days later on December 23, 1893, with J. W. Reinhart, John J. McCook and Joseph C. Wilson appointed as receivers. Union Pacific was another rival, but not that much of one, Union Pacific, or UP, was also in the western expansion and also was a route through the Rocky Mountains for industrial strength.

Expansion through mergers

Having completed a line to the West Coast, by 1886, William B. Strong started looking around for other expansion opportunities. The Financially troubled Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway Company, a Texas line with nearly 700 miles (1,100 km) of track in service provided just such an opportunity. The GC&SF was required, as part of a merger agreement, to construct a 171-mile (275 km) line from Fort Worth to Purcell, in the Indian Territory, where AT&SF had a railhead. The connection was completed, and the merger became official on April 27, 1887. GC&SF continued to operate as a wholly owned subsidiary until finally merged directly into ATSF in 1965, by which time it had about 1,800 miles (2,900 km) of track in service.

Santa Fe No. 2A, an EMC E1 is shown pulling the Super Chief on the cover of the railroad's 1945 promotional publication "Along Your Way."

| 1870 | 1945 | |

| Gross operating revenue | $182,580 | $528,080,530 |

|---|---|---|

| Total track length | 62 miles (100 km) | 13,115 miles (21,107 km) |

| Freight carried | 98,920 tons | 59,565,100 tons |

| Passengers carried | 33,630 | 11,264,000 |

| Locomotives owned | 6 | 1,759 |

| Unpowered rolling stock owned | 141 | 81,974 freight cars 1,436 passenger cars |

- Source: Santa Fe Railroad (1945), Along Your Way, Rand McNally, Chicago, Illinois.

Predecessors, subsidiary railroads, and leased lines

- Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway (1887–1965) — an operating subsidiary of ATSF

- California, Arizona and Santa Fe Railway (1911–1963) — a non-operating subsidiary of the ATSF

- Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway (1892–1911)

- Arizona and California Railway (1903–1905)

- Bradshaw Mountain Railroad (1902–1912) — a non-operating subsidiary

- Prescott and Eastern Railroad (1897–1911)

- Phoenix and Eastern Railroad (1895–1908)

- Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway (1892–1911)

- California Southern Railroad (1880–1906) — a subsidiary railroad chartered to build a rail connection between what has become the city of Barstow and San Diego, California

- Grand Canyon Railway (1901–1942) — became an operating subsidiary of the ATSF in 1902 and a non-operating subsidiary in 1924

- Santa Fe and Grand Canyon Railroad (1897–1901)

- Minkler Southern Railway Company (1913-1992?) — a subsidiary created to build the Porterville-Orosi District (Minkler to Ducor, California)

- New Mexico and Arizona Railroad (1882–1897) — ATSF subsidiary; (1897–1934) non-operating SP subsidiary

- New Mexico and Southern Pacific Railroad Company (1878-?) — a subsidiary created to lay track across the Raton Pass into New Mexico

- Santa Fe Pacific Railroad (1897–1902)

- Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (1880–1897)

- Sonora Railway — became an operating subsidiary of the ATSF in 1879

- Verde Valley Railway (1913–1942) — an ATSF "paper railroad" at Clarkdale, Arizona

- Western Arizona Railway (1906–1931) — an ATSF subsidiary (Kingman – Chloride)

- Arizona and Utah Railway (1899–1933) [2][dead link]

The failed SPSF merger

Main article: Southern Pacific Santa Fe Railroad

Santa Fe and Southern Pacific Railroad trains meet at Walong siding on the Tehachapi Loop in the late 1980s.

The companies were so confident that the merger would be approved they began repainting locomotives and non-revenue rolling stock in a new unified paint scheme. After the ICC's denial, railfans joked that SPSF really stood for "Shouldn't Paint So Fast." While the Southern Pacific was sold off, all of the California real estate holdings were consolidated in a new company, Catellus Development Corporation, making it the State's largest private landowner. Some time later, Catellus would purchase the Union Pacific Railroad's interest in the Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal (LAUPT).

The paint scheme that would never be completed is called Kodachrome. This is a much loved paint scheme and very few locomotives still bear this paint.

Merger into BNSF

Main article: BNSF Railway

On September 21, 1995 the ATSF merged with the Burlington Northern Railroad to form the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway. Some of the challenges resulting from the joining of the two companies included the establishment of a common dispatching system, the unionization of Santa Fe's non-union dispatchers, and incorporating the Santa Fe's train identification codes throughout.The merged railroads are now know as BNSF. There are multiple paint schemes bearing the BNSF logo. The most modern is the BNSF Swoosh scheme. This features an orange body with black letters and numbers. The logo has BNSF above a big triangle or swoosh.

Company officers

Presidents of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway:- Cyrus K. Holliday: 1860–1863

- Samuel C. Pomeroy: 1863–1868

- William F. Nast: September 1868

- Henry C. Lord: 1868–1869

- Henry Keyes: 1869–1870

- Ginery Twichell: 1870–1873

- Henry Strong: 1873–1874

- Thomas Nickerson: 1874–1880

- T. Jefferson Coolidge: 1880–1881

- William Barstow Strong: 1881–1889

- Allen Manvel: 1889–1893

- Joseph Reinhart: 1893–1894

- Aldace F. Walker: 1894–1895

- Edward Payson Ripley: 1896–1920

- William Benson Storey: 1920–1933

- Samuel T. Bledsoe: 1933–1939

- Edward J. Engel: 1939–1944

- Fred G. Gurley: 1944–1958

- Ernest S. Marsh: 1958–1967

- John Shedd Reed: 1967–1986[4]

- W. John Swartz: 1986–1988

- Mike Haverty: 1989–1991

- Robert Krebs: 1991–1995

Passenger train service

The cover of the railroad's November 29, 1942, passenger timetable. Vignettes of the American Southwest and Native American people were common in Santa Fe advertising.

In general, the same train name was used for both directions of a particular train. The exceptions to this rule included the Chicagoan and Kansas Cityan trains (both names referred to the same service, but the Chicagoan was the eastbound version, while the Kansas Cityan was the westbound version), and the Eastern Express and West Texas Express. All of the Santa Fe's trains that terminated in Chicago did so at Dearborn Station. Trains terminating in Los Angeles arrived at Santa Fe's La Grande Station until May, 1939, when the Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal (LAUPT) was opened.

To reach smaller communities, the railroad often operated Rail Diesel Cars (RDCs) for communities on the railroad, and bus connections were provided throughout the system via Santa Fe Trailways buses to other locations. These smaller trains generally were not named, only the train numbers were used to differentiate services.

The ubiquitous passenger service inspired the title of the 1946 Academy-Award-winning Johnny Mercer tune "On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe." The song was written in 1945 for the film The Harvey Girls, a story about the waitresses of the Fred Harvey Company's restaurants. It was sung in the film by Judy Garland and recorded by many other singers, including Bing Crosby. In the 1970s, the ATSF used Crosby's version in a commercial.

Courtesy of Wikipedia

No comments:

Post a Comment